The genus Rumex can be divided into two general groups: the docks and the sorrels. Both are delicious wild edible plants, and each group deserves its own article. Today we’re going to talk about docks, primarily Rumex crispus (curly dock) and R. obtusifolius (broad-leaved dock). The sorrels will get their own article as soon as possible.

Docks were widely eaten during the Depression, appreciated for their tart, lemony flavor, their abundance, and the fact that they were free for the taking. Today most people have forgotten about this common and tasty edible weed, but I gather enough every spring to blanch, freeze, and enjoy all year long.

Docks are perennial plants, most often found growing in neglected, disturbed ground like open fields, and drainages. Docks tolerate a wide range of moisture levels; they grow equally well in Pennsylvania (with 44″ inches of rain annually) and northern New Mexico (with 14″ of annual rainfall). Its taproot indicates that these are drought tolerant plants. Docks grow as basal rosettes of foliage in early spring; they are often one of the first greens to emerge. By early summer, dock produces tall flower stalks that bear copious amounts of seed, which can be dried and made into a gluten free flour.

The foliage of mature dock plants may be from 1-3 feet tall, depending on growing conditions, but in early spring, when it’s at its most delicious, the smaller plants can be hard to spot. Look for last year’s tall, reddish brown, flower stalks; these often remain standing over winter and new growth will emerge from the base of the stalk.

There are many edible docks, but curly dock and broad-leaved dock are the most common weeds in the USA and Europe. Other edible docks include R. occidentalis (western dock), R. longifolius (yard dock), and R. stenphyllus (field dock). R. hymenosepalus (wild rhubarb) is common in the desert Southwest and is larger and more succulent than many other docks. It has been a traditional food and dye source for several Native American tribes, and I’ve spotted it at Chaco Canyon. Next time I find it (NOT in a national park full of tourists and rangers), I’ll be sure to harvest.

Patience dock (R. patientia) was once cultivated as a vegetable in both the USA and Europe and is still grown as such by a small number of gardeners. If you read about a green called Patience, you’re reading about patience dock. Patience dock may be found as a feral plant, if you’re lucky. It’s larger, more tender, and perhaps more delicious than any other dock plant. You can find seeds for sale on line.

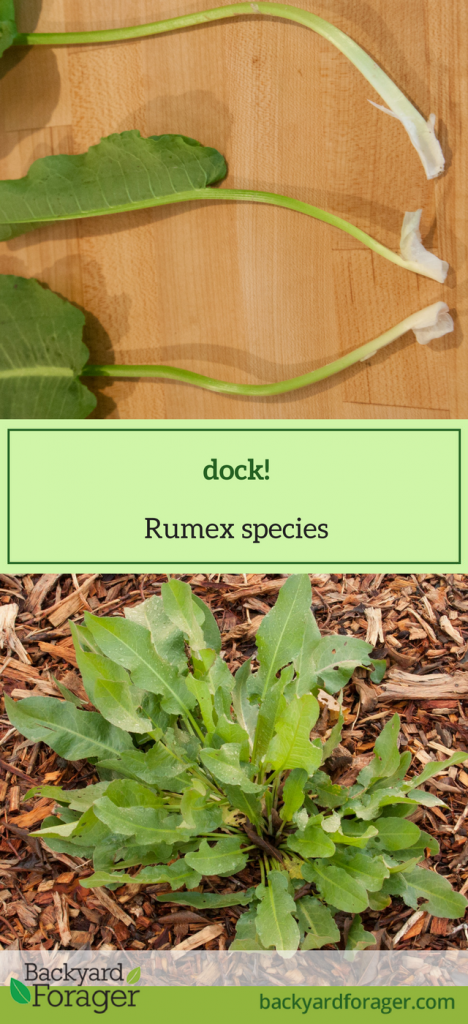

One of the best identification features for docks is a small, thin sheath that covers the base of each dock leaf. This is called the ocrea, and it turns brown as the plant ages. The condition of the ocrea can be a good indicator of how tender and tasty that dock plant is. A second excellent identification feature is the mucilaginous quality of the stems. The more sliminess you expose when picking dock, the more tender the greens will be. If you pick what you think is a young dock leaf but your hand isn’t covered with mucilage, you have not picked a young dock leaf.

The sour flavor of dock comes from oxalic acid, which may cause kidney stones when consumed in large quantities. The same compound is found in spinach. If your doctor has advised you not to eat spinach or if you are prone to kidney stones, don’t eat dock. If you are generally healthy and don’t gorge yourself on multiple pounds of dock every day for a month, you should be fine. If you are nervous about this, err on the side of caution.

Curly Dock

Curly dock may also be called yellow dock, sour dock, or narrowleaf dock, depending on where you live. Common names are tricky for that very reason; they change from place to place. If you want to be absolutely precise in describing which plant you’re using (or buying), use the botanical Latin name. That will be the same whether you’re in Umea, Sweden or Santa Fe, NM.

Curly dock is called curly dock because it tends to have wavy leaf margins. But the leaf shape is highly variable, both on a single plant, and from plant to plant. Younger plants tend to have foliage with less curly margins. Also, their leaves may be slightly rounder and broader than those of mature curly dock plants. Mature foliage is generally narrow with very wavy leaf margins.

The root of curly dock is yellow and intensely bitter. While it has traditionally been used for medicinal purposes, I prefer to use it in cocktail bitters.

Broad Leaf Dock

Broad leaf dock is similar to curly dock in its growth habit (taproot, mucilaginous) but its leaves lack the highly wavy margin of curly dock. Mature broad leaf dock leaves may have a slight wave to them, but not the serious undulation of curly dock. Additionally, broad leaf dock foliage is wider and more elliptical in shape than curly dock leaves.

Broad leaf dock is sometimes called bitter dock and while it’s true that mature leaves may be bitter, don’t forget that bitter leaves are some of our favorite greens. Arugula, dandelion, endive, and radicchio are all considered bitter greens and when cooked, they combine well with mild greens.

How & When to Harvest Dock

Both curly and broad leaf dock are edible at several stages. The most tender leaves and best lemony flavor comes from young leaves, before the flower stalk develops. Pick the two to six youngest leaves at the center of each clump. They may not even have fully unfurled and they will be very mucilaginous.

From early to mid spring, young leaves are tasty raw or cooked. If you want to use them raw, the mucilage can be a little overwhelming, so remove the leaf stem (petiole) and use only the actual leaves in salads. Larger petioles may be tough but pleasantly sour. But don’t throw them away! Consider chopping the petioles into small pieces, and cooking them as a substitute for rhubarb or Japanese knotweed.

Dry growing conditions and high temperatures generally produce more fibrous plant tissue and astringent flavor. Sample a leaf before picking. If the foliage seems a little tough but still has good flavor, it should be boiled or sautéed. The midribs of large dock leaves can be tough and fibrous, while the leaf blade remains tender. If you find a plant with tasty foliage but tough midribs, remove the midrib from the leaf before cooking.

Dock leaves are unusual in that when they are bruised, they may show red discoloration. These leaves, if otherwise young and fresh, are fine to eat.

By early summer, most docks will have flowered, at which point they are no longer tender wild greens. However, if you find a dock plant growing in cool shade that has not flowered even if it’s mid-July, try a leaf. It won’t hurt you, and if it’s still tender and tasty you’ll be glad you did. Once cool temperatures return in fall, dock obligingly puts out a second round of new growth. I usually gather a second harvest in October or November, depending on the weather.

In the Kitchen

Like so many greens, dock reduces in volume when cooked, to about 20-25% of its original volume. The application of heat also changes dock’s texture from slightly papery to creamy, and the color from bright green to a dull, brownish-green. Slight astringency in raw leaves may be transformed to mild lemony deliciousness by cooking, so if your raw harvest tastes only slightly astringent, consider using it as a cooked green. (If tasting the raw leaf causes you to make the Face of Disgust, it’s not worth bringing home to the kitchen.)

Dock greens are excellent in stir-fries, soups, stews, and egg dishes. I especially love dock with cream and cheese, and not just because cream and cheese are delicious. There’s something about the texture and flavor of cooked dock that works wonderfully with dairy. Dock custard surprises me with its outstanding flavor every time I taste it.

Because dock has a relatively short harvest season, like so many wild greens, harvest as much as you can when it’s at its peak, then blanch and freeze for later use. Dock is considered an invasive weed in fifteen states, so you probably won’t make a dent in the local population. And next February, when the promise of spring greens seems like a cruel culinary tease, you can pull a vacuum sealed bag of dock from your well-stocked chest freezer and bask in the glory that is Rumex.

Hi! Could you share your bitters recipe?

Sure! http://backyardforager.com/make-foraged-bitters/

Your link comes up as 404 NOT FOUND …?

Thanks for letting me know; I’ve fixed the link now, so you should be able to view the dock custard recipe. (It took me a while to figure out which link you meant! there are a lot in that post.)

Hi there, I find loads of Rumex spp with the seeds on, but cannot tell the different species. My question is whether all Rumes spp seeds are edible, and if so, how would you recommend they should be used, thanks!

All Rumex seeds are edible, but they vary in flavor, some being more bitter than others. So sample a few before you make a big harvest. If you haven’t read this post (https://backyardforage.wpengine.com/roasted-dock-seed-flour/), maybe it will help!

I just tried this link about Dock seed flour but it gives a 404 error.

Thanks so much for this wonderful accessible post about Docks!

Hi Amanda, I can’t recreate the 404 error. You’ve probably already tried clearing your cache, but if not, see if that helps. If not, you can always search for the dock flour post by entering those search terms in the search bar of the main blog page.

Thanks for the advice! I can’t wait to give it a try now, and will possibly start by making crackers first, although the flour will be another must, for sure!

When do you plant broadleaf dock in the garden as I bought some seeds

When you should plant depends primarily on where you are located. The seed packet should include information on planting time, which is often geared to your last frost date. Dock is perennial, but will still require certain temperatures to germinate. Did your seeds come in a printed packet? If so, that’s your best bet for information. If not, you’ll need to do a little research. I can’t speak from personal experience as I forage for it rather than grow it.

Thank you so.very much. Maria Stephens

I’m very excited to harvest some dock and try the custard, thank you for this lovely website! I was also interested in the gluten free flour link but it was broken. Would you be able to redirect me to it so I may explore? Much appreciated!

Thanks very much for letting me know, Adrianne. I’ve fixed the link and you should be able to access it now.

When I was growing up and had a few encounters with stinging nettle I was told to immediately rub dock leaves on the affected area as an antidote to the stinging. It seemed to work. Is there any evidence to this or was this just the placebo effect? Please and thank you.

I hear this a lot, and people also use jewelweed. I’ve never tried either, but if I had to guess, I’d say there’s probably some truth to it.

I just wanted to inform you that “The Spruce” website copied your article nearly word for word. I noticed they posted theirs in 2022 while you posted in 2018. I think its awful when companies do that.

Also, I enjoyed this article from you. I was raised to dry and eat the flowers but had no idea the leaves were edible too!

Thanks Muddy. I wrote that article for The Spruce; I’ll go look and see if they removed my byline.