Many foragers are also gardeners, and as one such forager/gardener, I only grow plants I can also eat. Most passers-by wouldn’t recognize my garden as edible, and that adds to the fun: I have a secret only other foragers would understand. I love seeking out ornamental edible plants that feed both body and soul. It’s also a practical decision since my garden is so teeny, it would be impossible to have separate spaces for food and for beauty. So let me introduce you to the chokeberry, aka Aronia melanocarpa, the newest addition to my edible garden.

Most people have never heard of chokeberry. If you say the word, they correct you, thinking you meant to say chokecherry, but these are two entirely different plants. Chokecherries (Prunus virginiana) are small trees that produce white, bottle-brush flowers followed by clusters of hanging fruit that look like miniature grapes. We are not here to discuss chokecherries. (Not today anyway.)

Chokeberry is the common name applied to A. melanocarpa and A. arbutifolia, both native to eastern North America. A. arbutifolia has red fruit while A. melanocarpa produces black fruit. Both are multi-stemmed shrubs, produce delicate, five-petaled white flowers in spring (pollinators love their open form with easy access to pollen and nectar), and have excellent fall foliage color. And while they are often found growing in moist soils, they are highly adaptable and quite drought tolerant, once established.

A naturally occurring hybrid known as A. prunifolia (aka A x floribunda) is sometimes mis-labelled as A. melanocarpa, and indeed, there is disagreement over whether it is its own, distinct species. While all aronia fruit is edible, I have only tasted the berries of A. melanocarpa, so let’s focus on that one.

Chokeberries get their common name from the astringency of their underripe fruit, and too many sources list the flavor of aronia fruit as unpleasant. Those sources are wrong. Like many wild fruits, aronia berries look ripe well before they actually are. Wait several weeks after the fruit turns black before tasting, to get the best possible flavor. Sure, the fruit contain lots of tannins, which are responsible for its mouth puckering quality. But when balanced with their natural sweetness, this makes for an interesting and enjoyable flavor. (Hey, wines have tannins, and you don’t hear people complaining about those.)

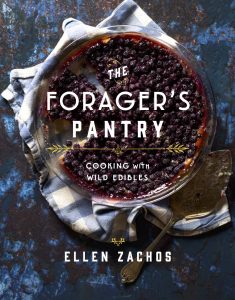

You’ll definitely want to add sugar to whatever you make with aronia fruit; it’s sour all on its own. When sweetened, it makes an excellent jam, jelly, wine, sorbet, ice cream, and the purple color of an aronia smoothie is outstanding. The seeds are insignificant, meaning you can use the pulp without having to run it through a food mill. Currently, my favorite way to use this fruit is in a clafouti, which is basically a large, creamy pancake.

Aronia has been grown as a commercial fruit crop for a hundred years in Eastern Europe, but North America is late to the party. Only now is it being touted as a superfruit due to its high levels of antioxidants. You can mail order whole fruit, powders, and extracts from multiple online sources, and yes, you can even trot on down to your local Trader Joe’s and buy yourself a bottle of aronia juice.

At a conference last year, Spring Meadows nursery gave me a new cultivar of A. melanocarpa: ‘Low-Scape Mound’. I was excited for two reasons: 1) I no longer live where I can forage for this fruit, and 2) this cultivar will actually fit in my garden! The straight species has an open and somewhat leggy growth habit, topping out at 4-6 feet tall, but ‘Low-Scape Mound’ grows to a maximum of 2 feet with a tighter, rounded growth habit. It’s a lovely shrub, easy to grow, and basically pest free, although sometimes browsed by deer and rabbits.

I wasn’t sure how it would do in Santa Fe, not only because our average rainfall (14″) is much lower than the average rainfall of its native range, but also because our soil here is on the alkaline side and aronias are native to acid soils. Happily, the plant has been a champ, doubling in size in a single growing season, and producing a small fruit crop, even in its first year. I would absolutely pay my hard-earned money for this plant.

Whether you forage for aronia or grow your own, look for berries to ripen in September or October. They may look ripe in August, but taste one before you harvest, just to be on the safe side. And harvest them as soon as they taste good…this is not a persistent fruit, and they’ll begin to dry and drop off the shrub within a few weeks of ripening.

Will this shrub do well In a container on a sometimes- windy ground-level terrace In NYC?

Yes. I’ve actually grown it in a container on a 17th floor terrace in NYC and it did very well.

J’ai cueillis les baies d’aronia trop tôt. Est-ce qu’elles peuvent continuer à mûrir après la cueillette ?

Malheureusement, je ne le pense pas. Je n’ai jamais essayé, mais si vous voulez essayer, mettez-les dans un sac (en papier) avec une banane ou une pomme pendant quelques jours. Cela fonctionne pour certains fruits, mais pas pour tous.